Circular Economy & Fashion

by Simon Seebaluck

Posted on: 03/12/2021

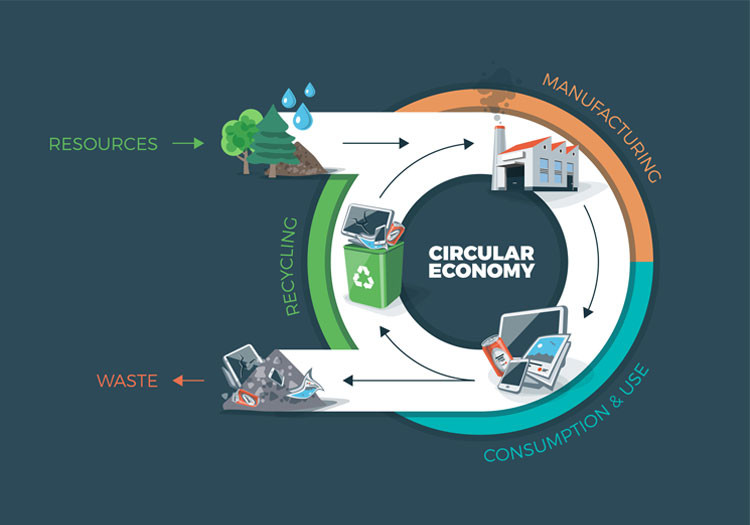

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF), annually this USD 2.5 trillion clothing industry hires over 300 million people along the value chain. Textile and clothing are a fundamental part of our everyday life, and a crucial sector in the global economy that has drifted far beyond just meeting basic human needs but also creating a negative impact on our planet. This system consists of using non-renewable resources extracted from the ground to make garments beyond what is required, often used for a short period, after which consumers dispose of what they no longer require, is discarded to landfills and incinerators. The prevailing system for producing, distributing, and how clothing is used operates in an almost linear way.

ISSUES

The fashion supply chain is one of the most globalized, intricated, and prolonged of any manufactured product, and by relying mostly on non-renewable resources – 98 million tonnes in total per year including oil are required to produce synthetic fibers (acrylic & nylon), fertilizers, and pesticides to grow cotton, and chemicals to produce, dye, and finish fibers and textiles. It is second to the oil industry in terms of environmental impact which also carries an immense footprint. The paucity of standards and regulations results in the inability of either governments or retailers to carry out any substantive enforcement on manufacturers.

The resulting sustainability issues of this multi-billion-dollar industry relate to serious consequences on society and the environment caused by water and food crises due to high water usage, ecosystem pollution including eutrophication (responsible for 20% of global water pollution), and the dispersal of hazardous chemicals (about 3,500 substances used in textiles of which 750 are classified as hazardous to humans and 440 to the environment), landfills, air pollution, and energy. All these are exacerbated by the problem of climate change with massive effect on water resources and agriculture, among others. Moreover, fiber cultivation for textiles essentially competes with food production for arable land and leads to food scarcity, and malnutrition, as well as substantial deforestation.

The fashion industry steers in a linear way, in a "cradle to grave" model whereby an expendable tradition spurs consumers to treat low-priced fast fashion items as throwaways. Furthermore, European consumers discard about a 5.8million tonnes of textiles each year which equates to an average of 11kg of textiles per person, with having worn garments only 7 or 8 times, although there has been a surge in apparel sales over the last two decades with a 40% rise in garments purchased per person. Each person spends around USD 1,050 annually on textile products representing 5.3% of their total expenditure on textile.

Over a decade, production has nearly doubled, propelled by a growing working-class population across the globe. This is mainly due to the 'fast fashion' phenomenon, with the quicker turnaround of new styles, increased number of seasonal collections, ease of purchase, and payment through one simple click, compounded by lower prices. As such, fast fashion encourages overconsumption and enhances waste generation, as this drives the promotion of new items and the disposal of old ones, which are branded as obsolete simply because they are out of fashion. Accordingly, some of the online brands mainly targeting young people are releasing between 12, 16, and 24 new clothing collections annually. Consequently, the increase in online sales has a large impact on resource use and emissions in terms of packaging and transport.

VISION

This overall concept consists of three design principles: a design for durability, design for long-lasting style, and design for disassembly (Circular Fashion, 2019). In this new vision, clothes are retained at their highest values during their usage and re-enter the economy after use by never-ending up as waste. To avoid that 15 million tons of clothes are sent to landfills, effective and appropriate solutions based on Systems Thinking should be seriously envisaged. If implemented, that might provide a driving force from a linear economy to a circular one, as otherwise, it would lead to a dystopian future.

Then again, eight African countries grew over 4% of global organic cotton production in 2017/18 and experienced a 20% increase over 2016/17. Regeneratively produced cotton is increasingly sought after and governments as well as businesses have an opportunity to respond to market demand by incentivising and investing in growing material inputs in line with biodiversity protection. Using local raw materials in manufacturing can lower climate impacts from transport emissions, increase the traceability in the supply chain, and increase the embedded value of the products.

Consequently, Systems Thinking can provide a driving force for a quantum leap from a linear economy to a circular one and how appropriate knowledge and enabling infrastructure may assist in enhancing circularity. Below are some focus areas where such vision can be realized.

Focus Areas:

1. New business models

Business models such as rental, repairs, and sharing can give customers more flexibility on the clothes they would like to wear. A study performed by the EMF pointed out that if the number of times a garment is worn were doubled, and garment purchases and production were reduced by half as a consequence, the greenhouse gas emissions of the textiles industry would be reduced by 44 percent (EMF, 2017). Circular business examples in the textile industry are by no means new in Africa – on the contrary, they are culturally embedded and could enhance consumer’s emotional attachment to clothes. There is a lot of know-how and skills among tailors and designers across the African continent who design, make, remake, and repair clothes on a daily basis, generating employment.

2. Make durability attractive

Clothes are designed and produced at high quality by using better yarns and ecological finishing processes. The choice of materials is an important factor that will ensure sustainability as well as durability. Different fibers produced from different resources will have different environmental and climate impacts. The aim is to increase the lifespan of garments through durable fasteners, availability of spare parts, colorfastness, and fabric resilience.

3. Design out waste and pollution

Designing fabrics by eliminating the use of toxic dyes and garments using nickel-free metalware. Designers accepting a wider shade tolerance and adjust washing standards according to shade levels. This would avoid millions of fabrics being rejected or worse; redyed. Designers to use near-matching factory available stock threads rather be persistent on what the design boards stipulate, especially in Denim where the wash will inherently fade the indigo away. This could help alleviate massive thread stock levels and unnecessary thread production, where excessive dyes, water, and transportation are involved.

4. Regenerate natural systems by saving water

Denim fabrics production is a highly complex process that involves many steps of interaction before reaching the full garment status. Thus, the fabric dyeing process involves excessive water, and chemicals consumption, and disproportionate water level to remove the same indigo at a garment finishing/laundry stage (Fabric finishing 70L/Meter, Utilities 20L/Meter, Garment finishing 75L/Meter). The Ozone technology (G2 Dynamic from Jeanologia, Spain) is a major positive disruptor to the Denim fabric process. Using Ozone created from the air in the atmosphere, G2 Dynamic reduces 95% of the conventional water consumption, without the use of thermal energy, and no chemicals. In addition, Jeans could also be finished with the same Ozone technology where less water (the conventional process of 90L/Jeans reduced to 15 L) and no chemicals are required in the laundry. With such a qualitative technological leap, Jeanologia estimates that it could save an average of 8.8 million of m3 of water annually which is sufficient to supply the entire population of Uruguay. Such technological innovation will generate less waste, and fewer emissions while phasing out hazardous chemicals, not to mention increasing availability of the precious liquid for portable purposes.

5. Consumer education

An EIM (Environmental Impact Measuring, developed by Jeanologia) could be labeled on each garment or a quick response (QR) code can also provide transparent information on water use; limited use of hazardous substances, reduced emissions to water and air during production, prolonging the product lifetimes, take-back systems, re‐design, and fiber composition. Such information could be helpful for the consumer to be consciously aware of the full environmental impact of the garment before engaging in a buying decision.

OVERALL

As exigencies grow, the prevalent textile and fashion course is set to have calamitous ramifications for us and beyond. It is a prodigal system that poses pressure on resources, contaminates, and eventually degrades the natural environment by generating significant and growing negative societal burdens. A shift to a circular system entails a thorough systemic change throughout the whole value chain supported by adequate policies from governments, brands, retailers, manufacturers, and consumers rather than just small-scale initiatives and isolated success stories. The transition to a circular system for textiles could be escalated by deploying policies aimed at technological and business model innovation, such as R&D subsidies, and investment support for SMEs. Therefore, it is mandatory to reach a change in behavioral attitude through sustainability awareness via education and training of both the consumers and the producers, notably towards durability, reuse, repair, and recycling. Finally, at the global level, such a circular and sustainable system would contribute towards achieving quite a number of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, and Goal 13: Climate Action, among others.

Original Link: https://api.abana.mu/media/report-attachment/61a4772f1920e546705140.pdf